Carrion beetles – Nature’s clean-up crew

Meet the unsung heroes of the natural world: Carrion beetles. Important decomposers and recyclers, most Carrion beetles feed and breed on dead animals. Ashleigh Whiffin, Curator of Entomology at National Museums Scotland, and Carrion beetle specialist, introduces us to Nature’s very own clean-up crew.

A Common Burying beetle (Nicrophorus vespilloides) examining a small mammal corpse. Image: © Richard Whitson

Classification

- Kingdom

- Animalia

- Phylum

- Arthropoda

- Class

- Insecta

- Order

- Coleoptera

- Family

- Staphylinidae

- Genus

- Species

The naming of bugs is a difficult matter

Up to January 2025 Carrion beetles formed the Silphidae family. However, this classification has been modified: Silphidae are now considered a subfamily of Staphylinidae and the subfamilies Nicrophorinae and Silphinae are now tribes Nicrophorini and Silphini (see Sikes DS et al.). Since this is a very recent development, many online and print publications may still reflect the old classification.

Carrion beetles carry a faint odor of death. As their name suggests, most of the group are associated with dead animals. They might not live the most glamorous lifestyle but, as nature’s undertakers, many Carrion beetles perform an essential job – removing rotting corpses from the environment, reducing the spread of disease and using the dead to create new life.

The Nicrophorus species are well known for their ability to bury dead birds and small mammals (such as mice or voles). This gives them their other common name of ‘Burying beetles’. Sensitive chemo-receptors on the beetles antennae, detect the sulphur-containing compounds released by carrion and enable the beetles to locate a dead animal up to several kilometers away. When a male beetle finds carrion, he releases a pheromone from his abdomen to lure in a female. Once he successfully secures a mate, the pair copulate and get to work creating a home.

Since carrion is an ephemeral resource, the beetles must act quickly to conceal their find, to avoid competition from other scavengers. The pair work together, excavating soil from beneath the corpse, until it disappears. Strong and efficient, they’re capable of burying remains up to 30 times their own weight and complete the process in just five to eight hours!

If that’s not impressive enough, these beetles are also devoted parents. The male and female work together to prepare the dead animal, transforming it into an underground nest. They coat the carcass in anti-microbial secretions which help to slow the decomposition and they defend the nest against rival insects. They even helpfully pre-digest rotting flesh and regurgitate it to their offspring. Can you say the same about your parents?

As well as this endearing behavior, their habit of burying carrion means that they play an important role in the recycling of dead animals and are vital in maintaining a healthy ecosystem. They’ve been at it a long time, too! Evidence from the fossil record shows that Carrion beetles existed during the middle Jurassic (165 million years ago) and may have played an important role in the decomposition of dinosaurs and early mammals.

A pair of Common Burying beetles (Nicrophorus vespilloides) tending to their offspring. Image: © Tom Ratz

Carrion beetles, particularly the Burying beetles (Nicrophorus spp.) are often observed carrying phoretic mites (Poecilochirus sp.; acari: parasitidae) on their backs. These hitchhikers are also seeking carrion, as they prey on the eggs or small larvae of carrion flies.

This relationship was long considered to be mutualistic, with the beetles serving as a form of transportation and the mites assisting the beetles by reducing the competition for the carrion. However, some studies have demonstrated that this relationship is not always beneficial to the beetle, as some mite species will feed on the eggs of the Burying beetles.

A Common Burying beetle carrying some mite passengers. Image: © Liam Olds.

A diverse family

Globally, nearly 200 species of Carrion beetles are known, with only 21 recorded in Great Britain.. Several are widespread and common in domestic gardens, parks and woodland. Some of them are also attracted to light, like moths, so they occasionally gather at outdoor lights or wander into buildings.

The most frequently encountered Burying beetle is ‘The Undertaker’ (Nicrophours humator), a large beetle, smartly dressed head to toe in black, except for its clubbed orange antenna. A close second is the Banded Burying beetle (Nicrophorus investigator), also with orange antennal clubs. This is one of five species with striking orange markings on its wing cases (elytra) which act as a warning to predators.

Left: The Undertaker (Nicrophours humator). Right: The Banded Burying beetle (Nicrophorus investigator). Image: © NMS

Species such as the Shore Sexton beetle (Necrodes littoralis) are not such invested parents. Their offspring feed on larger carrion above ground, again fulfilling an essential decomposer role.

That is, unless they are tricked by a Corpse flower (Amorphophallus titanum) like the one that visited the Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh (RBGE), in 2019. It may go without saying, that this impressively stinky plant is not native to Scotland. In the wilds of Indonesia, where it naturally occurs, it uses a putrid odour to attract carrion insects, including a closely related beetle species (Diamesus osculans) which is thought to be one of the pollinators of this plant.

Did you know?

Corpse flowers are cultivated also in Switzerland. In 2023, a corpse flower bloomed at the botanical gardens in Zurich, Basel, and at Papillorama in Kerzers.

Left: A female Carrion beetle (Necrodes littoralis), attracted to the Corpse flower at RBGE. Right: A close-up of the same beetle. Image: © Ashleigh Whiffin

Despite being called Carrion beetles, this fascinating group also contains a few species that don’t feed on carrion at all. Some are solely predatory, like the Common Snail Hunter (Phosphuga atrata). This perfectly adapted predator of snails releases digestive enzymes to break through the defensive mucus and digest the flesh, its skinny head enabling feeding access. Then, there’s the strikingly marked Caterpillar Hunter (Dendroxena quadrimaculata), which prowls the canopy of oak trees searching for moth caterpillars.

A Common Snail Hunter (Phosphuga atrata) in action. Image: © Maria Justamond.

To add another lifestyle into the mix, there’s also a species that is phytophagous (vegetarian)! The Golden beetle (Aclypea opaca) is particularly partial to sugar beet and brassicas. What a diverse bunch!

A specimen of Phosphuga atrata from the NMS collection. Image: © NMS

The collection of National Museums Scotland (NMS)

The museum’s collection is a treasure trove of information. Each of our preserved insect specimens is accompanied by data labels that tell us where and when the insect was found, what it was associated with, and who it was collected by. This provides valuable and concrete evidence that a species occurred in a particular place at that point in time.

Extracting this data from the labels means we can compile information that tells us more about species distribution and allows us to observe any changes that have occurred over the years. This information, alongside current recording, is a vital part of informing conservation efforts.

Part of the NMS collection of Carrion beetles (subfamily Silphinae). Image: © Ashleigh Whiffin

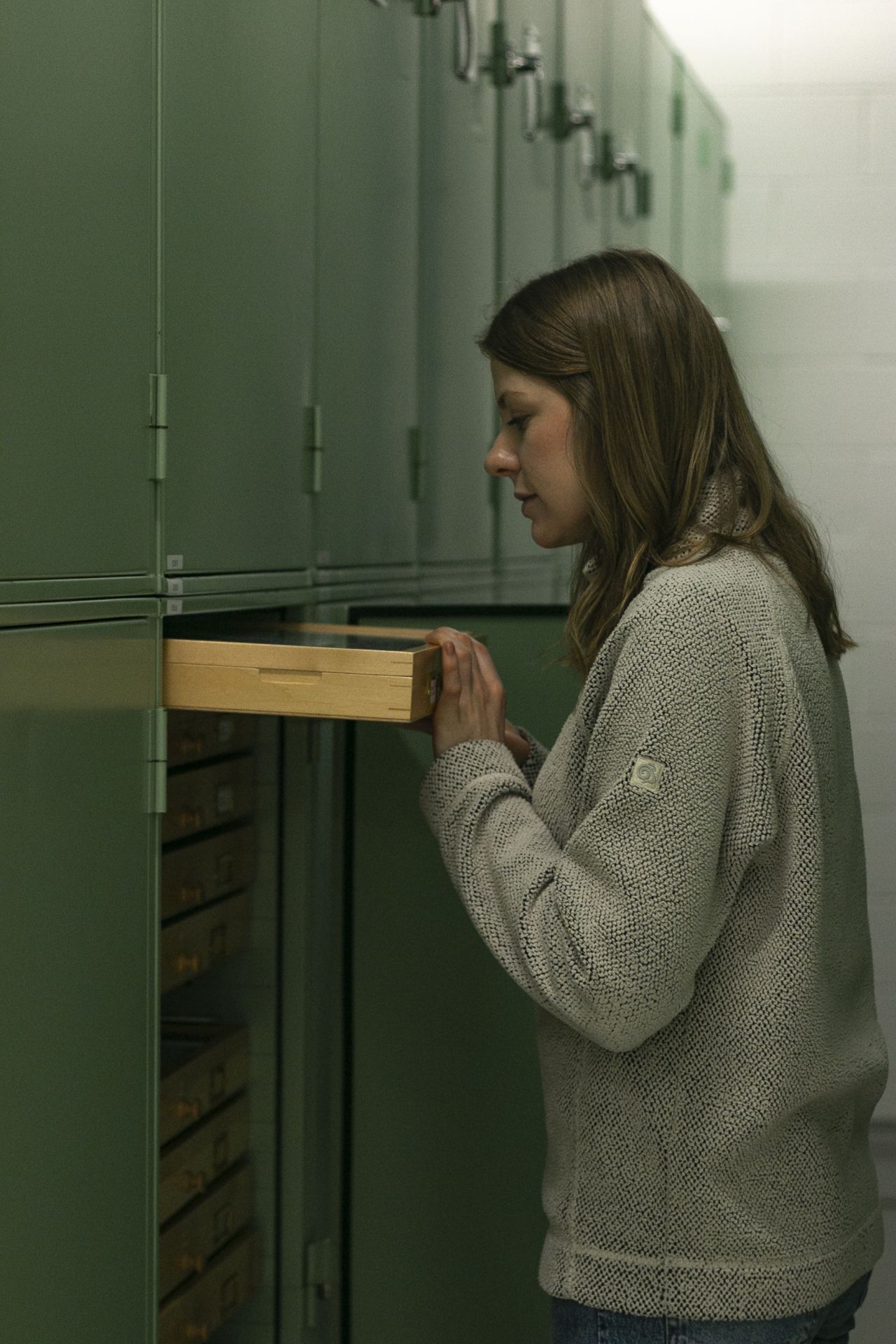

Our collection contains examples of Carrion beetles from around the world, but the majority were collected in Scotland. I have databased our collection of 800 British and Irish specimens to extract the useful ecological information associated with them. During this process, I came across some particularly interesting examples, such as a specimen collected in 1840 by the Rev. W.D. Fox: Charles Darwin’s second cousin! These historic records now form part of the national dataset for Carrion beetles which is part of our overarching mission to digitise our specimens, making our collection more accessible for research.

Databasing historical specimens from the collection. Image: © Ashleigh Whiffin

In my spare time, I volunteer as co-organizer of the Carrion Beetle Recording Scheme, one of many citizen science initiatives, working to encourage recording of the lesser-known insect groups. We have been collating records of Carrion beetles since 2016 to better understand their ecology, distribution and conservation status.

Read more about Ashleigh’'s work here.

Thanks to a community of dedicated biological recorders, the scheme has accrued over 30 000 records, enabling the creation of an atlas. However, there is still much work to be done and we’re keen to get as many people recording these beetles as possible! If you’d like to learn how to identify them, there are free resources available on the recording schemes webpage.

CSI beetles

As many of these beetles are attracted to the dead, another incredible benefit they bring to the table is that they can provide useful evidence in death investigations. Their presence on a corpse can help to establish the minimum post-mortem interval – in other words, the time elapsed since death. By ensuring that our knowledge of Carrion beetle distributions and distributions and the environmental and the seasonal effects on their life cycle is detailed and accurate, this data could be beneficial to investigators.

Read more about forensic entomology in our article “Dr. Amoret Whitaker – Crime Scene Insects".

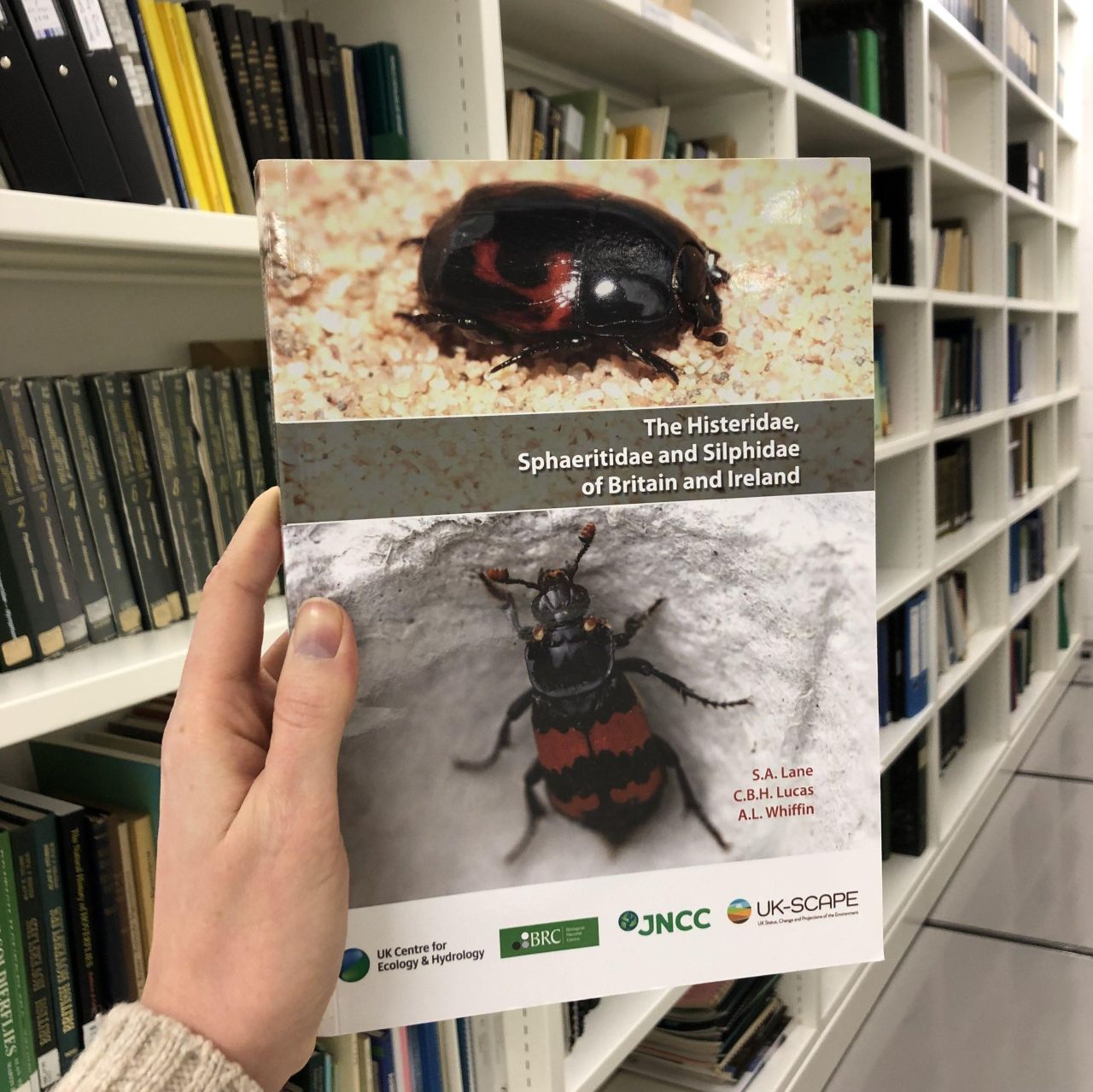

A comprehensive atlas covering 75 species across three charismatic beetle families. Note: This book was published before the change to the taxonomic classification (demoting Silphidae to subfamily level and placing them within the Staphylinidae)! Image: © Ashleigh Whiffin

While decomposers tend not to get as much publicity as their pollinator counterparts, they are equally as important and are much deserving of our respect. A world without Carrion beetles and other decomposers would be a pretty awful place to be!

*Glossary

Phoretic: When an animal species uses another animal species for transportation without harming it.

References

Beninger CW 1993. Egg Predation by Poecilochirus carabi (Mesostigmata: Parasitidae) and its Effect on Reproduction of Nicrophorus vespilloides (Coleoptera: Silphidae), Environmental Entomology, 22;4:766-769. https://doi.org/10.1093/ee/22.4.766

Cai C et al. 2014. Early origin of parental care in Mesozoic carrion beetles, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111;39:14170-14174. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1412280111

Lane SA et al. 2020. The Histeridae, Sphaeritidae and Silphidae of Britain and Ireland. Field Studies Publications, Telford.

Sikes DS et al. 2024. Large carrion and burying beetles evolved from Staphylinidae (Coleoptera, Staphylinidae, Silphinae): a review of the evidence. ZooKeys 1200:159-182. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.1200.122835

Claudel C. 2021. The many elusive pollinators in the genus Amorphophallus. Arthropod-Plant Interactions. 15:833-844. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11829-021-09865-x