Aphids: Tiny insects with giant impact

Yes, aphids are a nuisance when you grow plants. But what amazing creatures they are!

An adult female pea aphid (Acyrthosiphon pisum) is followed by nine newborns, neatly lined up on a plant stem. This formation is no coincidence – staying close to their mother not only shields these nymphs from predators but also positions them at prime feeding locations. Image: © Patricia Sanches

Profile

- Diversity: There are over 4 000 identified aphid species, with 250 recognized as significant pests in ornamental horticulture and agriculture.

- Distribution: Aphids are found worldwide, with greatest diversity in temperate regions.

- Ecological impact: They play a crucial role in ecological networks involving plants, other insects, and pathogens.

- Economic impact: Uncontrolled aphid populations can cause up to 80% crop yield losses, translating into millions in financial losses annually.

What are aphids?

Aphids are small (2–4 mm long) pear-shaped insects, notable for their soft bodies, long legs, and antennae. They display a remarkable variety of colors, ranging from white and gray to vibrant yellow and pink, and some feature a protective waxy or woolly coating, as seen in “woolly aphids”. Most aphids are easily recognized by their two protruding tubes at their back end, called siphunculi or cornicles, which presumably release chemical compounds that deter natural enemies.

An aphid is sucking a plant sap. One can observe the siphunculi at their back. Image: Wikipedia Commons/Sanjay Acharya, CC license.

Another feature relevant for aphid characterization and ecological interactions is their syringe-like stylet (mouthparts), which allows aphids to pierce plant tissues and feed on sugary sap. As they feed, aphids release honeydew. This sugary excretion supports pathogenic fungal growth and serves as a food source for other insects, such as ants that keep aphids as livestock. (Read more about this in our article “Two-faced ants”.)

The versatile life cycle of aphids

Aphids exhibit a remarkably complex life cycle with up to 40 generations annually which depending on the species differs in factors such as the change of host plants and the presence of a sexual phase.

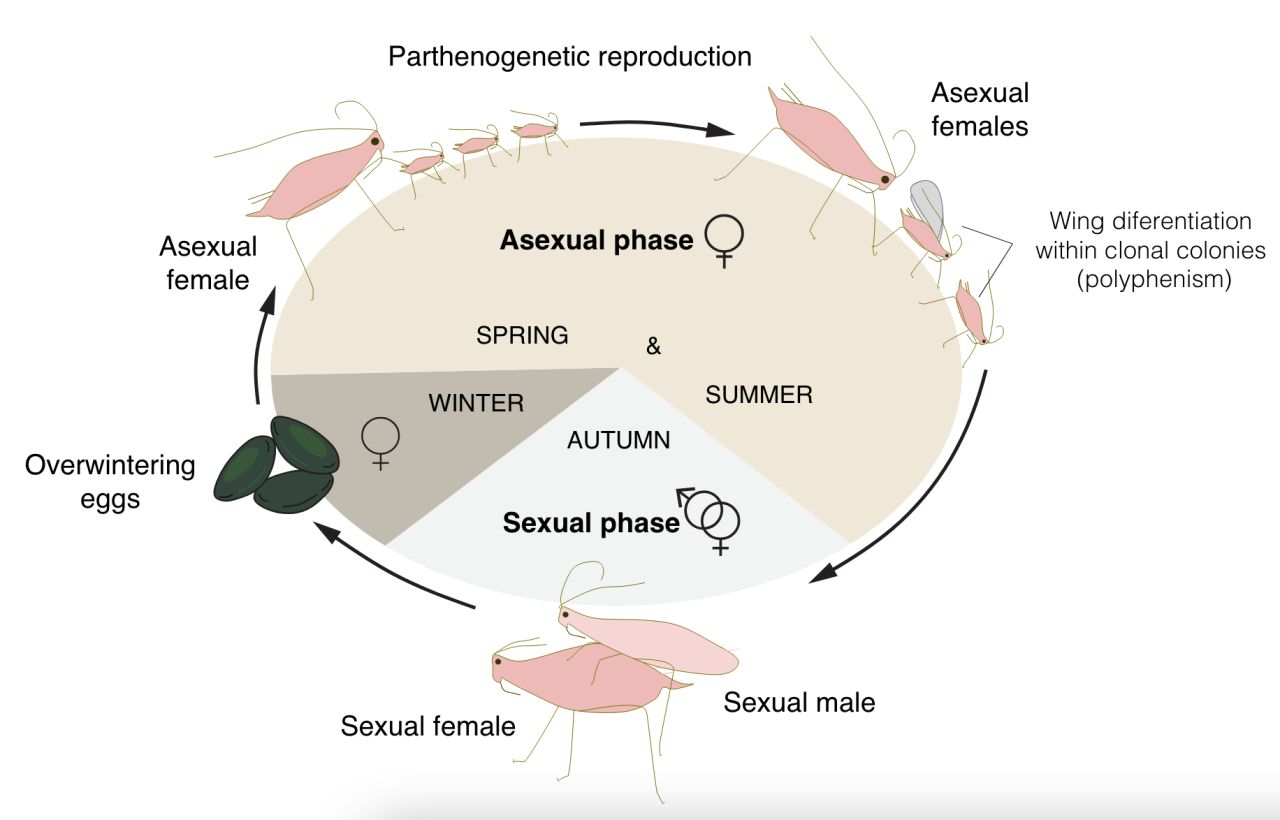

A simplified life cycle of an aphid begins in early spring when an asexual female hatches from an overwintering egg. Throughout the warmer months of spring and summer, these asexual females engage in prolific reproduction, giving birth to live nymphs (young aphids) daily without the need for mating (through a process known as cyclic parthenogenesis). These nymphs, which closely resemble adults, mature in about 10 days, and start to reproduce themselves. During this asexual phase, aphids can exhibit extraordinary adaptive responses under conditions of food deprivation or crowding stress, including the appearance of clonal individuals with wings (known as a type of polyphenism*) that can disperse and infest brand-new plants. As autumn approaches, some species undergo a sexual phase, producing males and females that mate to lay overwintering eggs, completing the life cycle.

Aphid life cycle. Image: © Patricia Sanches

Just like a Matryoshka doll

Imagine a Matryoshka doll, consisting of a set of nested dolls where each one opens to reveal a smaller one inside. Did you know that aphid asexual reproduction can be just like that? This phenomenon, called by scientists "telescoping of generations", occurs because aphids in the asexual phase give birth to live nymphs instead of eggs, and, for that, these females must carry developing embryos within their bodies. Astonishingly, these developing embryos already contain embryos within themselves, reminiscent of a Matryoshka doll! In other words, aphids can be born pregnant, and an adult aphid can simultaneously carry embryos of both its daughters and granddaughters.

A Matryoshka doll. Image: Adobe Stock

Sweet but feared

The aphids’ appetite for plant sap is feared. Although a single aphid’s feeding typically results in minor plant damage, large populations can severely drain a plant’s energy resources, reduce growth, or even cause death. Moreover, excessive honeydew secretion can promote mold growth, leading to wilt and other problems. Despite these issues, the most significant threat aphids pose, particularly in agriculture, arises from their specialized feeding pattern. Like blood-feeding insects, aphids feeding on plant sap are effective vectors, transmitting over 50% of all plant viruses carried by vectors, making them major agents of disease in the plant world. Read more about the aphids’ armory in our article “The clone wars on planet plant”.

Bug Off: Dealing with aphid infestations

Early detection is critical for effectively managing aphid infestations. For minor outbreaks in gardens, aphids can be controlled by manual removal or by spraying them with a strong stream of water. Alternatives such as diluted soap sprays or neem oil effectively kill aphids on contact. Additionally, gardens can be further safeguarded by including plants that attract natural enemies of aphids (clover, mint, and dill), or those that typically repel aphids (catnip and garlic).

Beneficial insects are a viable option for mitigating aphids in both gardens and agricultural crops. Currently, there are many insects commercially available that can naturally reduce aphid populations, including ladybugs, lacewings, and parasitic wasps.

A wasp is parasitizing aphids. Video: © Patricia Sanches

Finally, chemical control is very effective for more persistent infestations. Alternative options include systemic insecticides that are absorbed by the plant and affect pests that feed on its sap, making them less harmful for other species.

Did you know?

Aphid producing honeydew in slow motion. Video: © Patricia Sanches

Not all honey comes from flowers. While bees typically collect nectar from various flowers to produce honey, flower availability can be limited, especially in forested areas or towards the end of the blooming season. So, how do bees make honey when flowers are scarce? Bees can display fascinating behaviors in times of scarcity (read more about this in our article "The resourceful buff-tailed bumblebee". During such times, bees can be spotted gathering honeydew, the sugary excretion released by aphids and other sap-feeding insects, as an alternative source for their honey production. Though not the bees' preferred method, this beautifully illustrates how something that is essentially waste for some can turn into a valuable treasure for others. In fact, this delicatesse, known as 'honeydew honey,' is even available commercially in many specialty shops.

*Glossary

Polyphenism: a phenomenon where clonal individuals (same genotype) display different characteristics (different phenotypes) due to environmental conditions, such as food availability, competition from overpopulation, abiotic factors, etc.

References

Stares C 2017. Sticky solution: aphids' honeydew suits the bees. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2017/jun/09/sticky-solution-aphids-honeydew-suits-bees-country-diary Accessed 29.4.24

Loxdale HD et al. 2020. Aphids in focus: unravelling their complex ecology and evolution using genetic and molecular approaches. Biological Journal of the Linnean society 129(3):507-31. https://doi.org/10.1093/biolinnean/blz194

Meiners JM et al. 2017. Bees without flowers: before peak bloom, diverse native bees find insect-produced honeydew sugars. The American Naturalist 190(2):281-91. https://doi.org/10.1086/692437

Simon JC and Peccoud J 2018. Rapid evolution of aphid pests in agricultural environments. Current opinion in insect science 26:17-24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cois.2017.12.009

Van Emden HF and Harrington R (editors) 2017. Aphids as crop pests. Cabi https://doi.org/10.1079/9781780647098.0000