The golden ground beetle – An ally in your garden battle

With its shiny green armor, strong mandibles and impressive size, the golden ground beetle certainly attracts attention. But there is no need to be nervous. This beetle is the gardener’s friend and will leave you in peace if you treat it gently.

The golden ground beetle can become unpleasant when attacked but is usually harmless and even beneficial to humans. Image: Adobe Stock

Profile

- The golden ground beetle belongs to the genus Carabus in the family of the Carabidae. Dispersion took place millions of years ago via a flying ancestor.

- The genus Carabus is highly diverse with almost 1 000 species spread over Eurasia.

- Carabus species display an astonishing diversity of colors: from pitch black to a variety of metallic colors mixing green, copper, purple and blue.

- Most Carabus species lack wings, hence their ability to disperse is limited. This is thought to have contributed to the great species diversity of the genus, and its adaptation to different habitats: from forests to open fields, and from low- to highlands and alpine habitats.

- C. auratus beetles are a beautiful green-copper metallic color and can reach an impressive size of 2 to 3 cm.

- Unlike most Carabus beetles, C. auratus is day-active and can therefore be readily spotted in open field habitats such as gardens, (alpine) meadows, and pastures.

Classification

- Kingdom

- Animalia

- Phylum

- Arthropoda

- Class

- Insecta

- Order

- Coleoptera

- Family

- Carabidae

- Genus

- Carabus

- Species

- C. auratus

Life cycle of carabus auratus

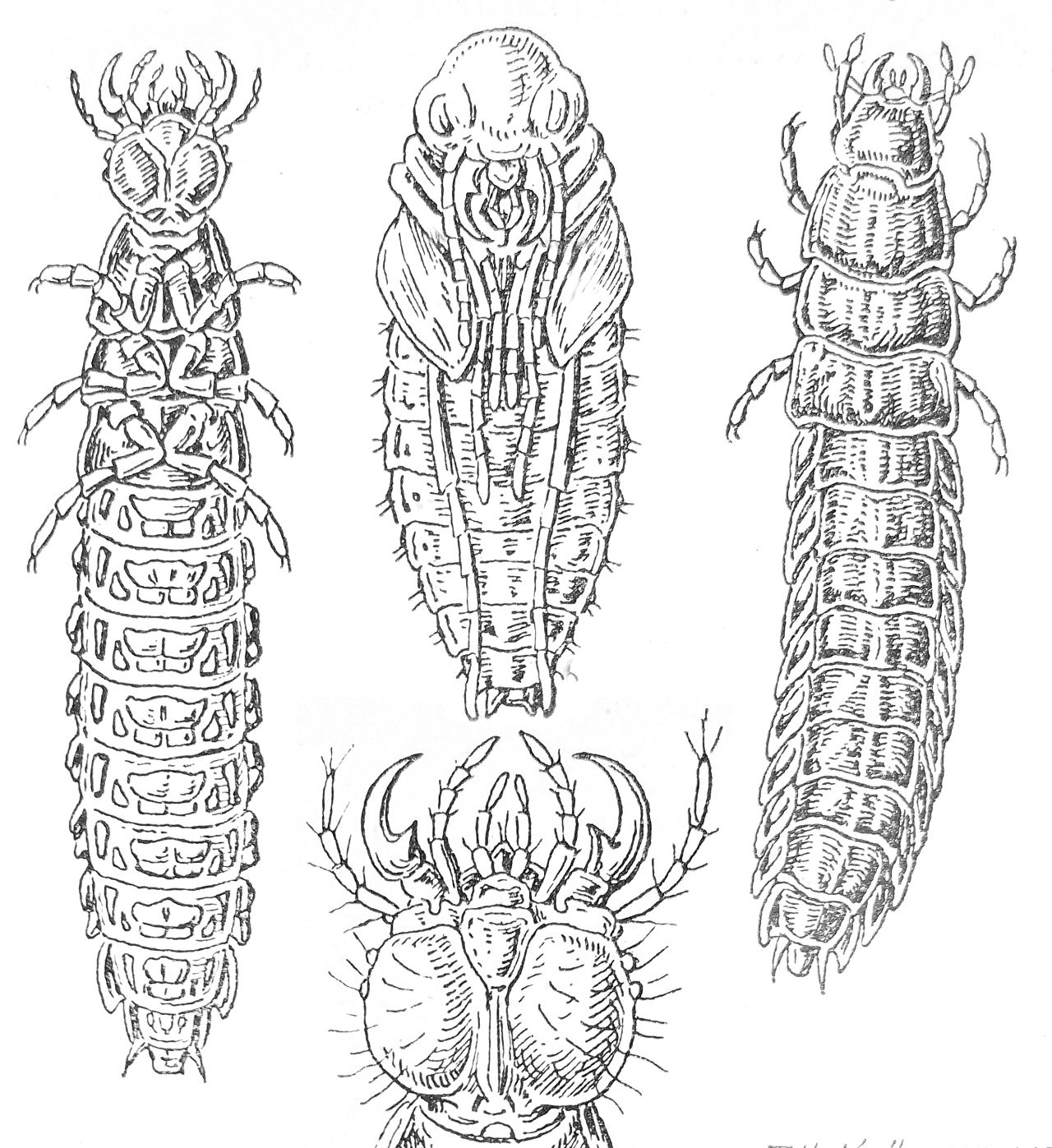

Adult golden ground beetles mate in spring after hibernation. They lay single eggs or small batches of eggs in moist soil. The larvae are black, long and slender, and more elusive than the adults; they are mainly active at dusk and dawn hunting earthworms and small insects. They pupate in late summer, and the new generation of adults emerges in autumn when they quickly set off in search of a hibernation spot under rocks, mosses or in the soil. They can live up to three years.

Illustration of Carabus auratus larva and pupa. Image: Wikimedia Commons, CC license

Who’s afraid of Carabus auratus?

The golden ground beetle can easily be mistaken for a foe. Due to their size and large mandibles, golden ground beetles are certainly intimidating. When picked up, they might bite with their powerful mandibles, which, together with an enzyme-rich liquid they eject, can cause slight pain but no serious injury. In addition, they can expel a foul-smelling and corrosive liquid from the tip of their abdomen when feeling threatened. But when handled with care, these beetles pose no threat to humans at all and are wonderful to observe up close in the palm of your hand.

It is a different story as far as their prey is concerned, though. Both adult and larval Carabus are predatory. They hunt a variety of prey, including earthworms, snails and slugs, and other insects such as caterpillars. Prey is cut to pieces by the mandibles and the flesh is liquified and predigested by the above-mentioned enzyme-rich liquid so that it can be easily consumed. Most Carabus species are nocturnal. This is likely because many of their prey are night-active (snails and slugs, many caterpillar species) but also to avoid their own predators: amphibians, birds, and insect-feeding mammals. Hence, Carabus beetles occupy an important place in the food web as predators of herbivores and prey of higher-order predators.

A friend who needs help

Its appetite for herbivores makes the golden ground beetle an ally in our gardens, and more broadly in our battle against agricultural pests. Historically, these beetles were released in gardens to get rid of snails and slugs. With their love for caterpillars and beetle larvae, they are the ideal natural enemies for controlling many agricultural pests, such as the larvae of the Colorado potato beetle (Leptinotarsa decemlineata, a vicious pest of potato), and potentially important players in sustainable biological control strategies.

Unfortunately, the numbers of the golden ground beetle have been declining over the last decades. As many other insects, they suffer from the widespread use of pesticides and the intensification of agriculture. Golden ground beetles need a diverse landscape to thrive: landscape elements such as hedges, trees, and stones are essential as they provide hiding places, prey, and overwintering habitats.

Why so shiny?

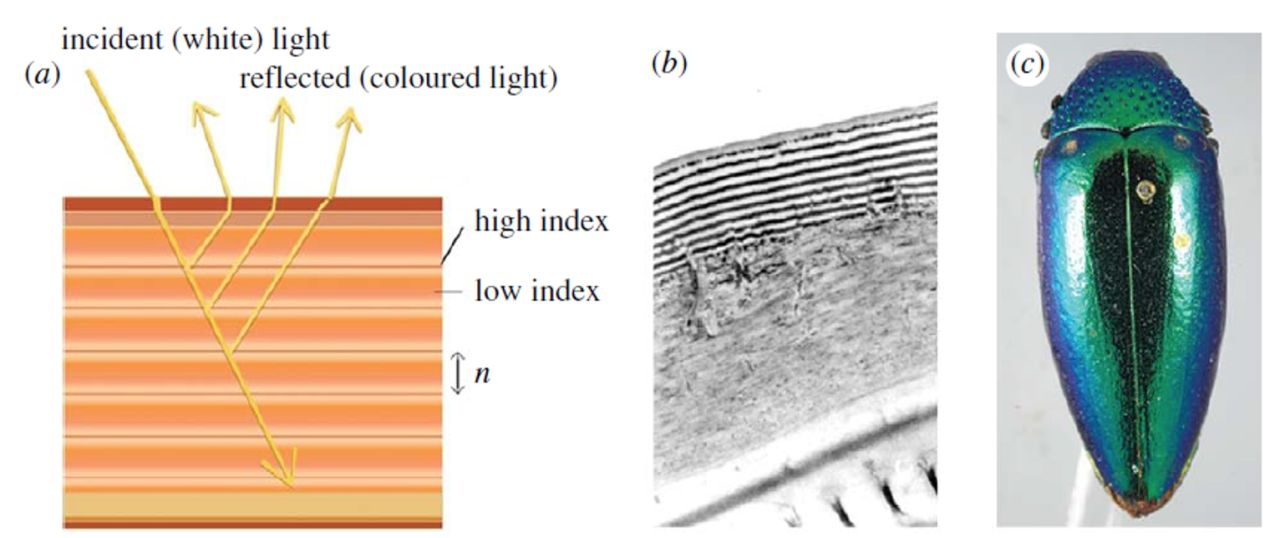

Although the golden ground beetle is a ferocious predator, it has enemies of its own: amphibians, birds, and insect-feeding mammals. Like knights in battle, golden ground beetles are protected by shining armor against enemies. This armor is formed by the elytra – the modified and hardened front wings – and it protects the hindwings and the abdomen (the part of the insect body containing the most vital organs). The hindwings of the golden ground beetle, however, are reduced and it cannot fly. The shiny golden-green color of the golden ground beetle’s elytra is produced by multilayer reflectors: Multiple layers of chitin (the polymer that the exoskeletons of insects and crustaceans consist of) reflect the light to produce iridescence coloration (see image below). This mechanism was first mentioned for C. auratus by the German comparative anatomist and physiologist Carl Friedrich Wilhelm Krukenberg in 1880! Now, why does this beetle’s armor shine golden-green? The function of iridescence coloration has been, and still is, debated in the scientific literature. Although no studies have been performed on the golden ground beetle, a recent study on the Asian jewel beetle Sternocera aequisignata provides strong evidence that iridescence coloration provides protection against larger predators like birds as it allows the insect to camouflage, especially against glossy backgrounds like reflecting leaves. Hence, although the armor may look flashy and conspicuous to us, it may help the golden ground beetle hide from larger predators. Other functions of iridescent coloration include thermo- and water regulation.

Multilayer reflector. (a) Schematic of thin chitin layers reflecting the light, (b) TEM* (Transmission Electron Microscopy) cross section of chitin layers building up a multilayer reflector in the festive tiger beetle (Cicindela scutellaris), (c) iridescent color in a buprestid. Image: Adapted from Seago et al. 2009.

*Glossary

TEM, Transmission Electron Microscopy: In TEM an accelerated electron beam passes through a thin specimen and creates an image allowing to study its structure and morphology. The operating principle is explained in this video: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Transmission_Electron_Microscope_operating_principle.ogv

References

Blanc M & Toussaint E 2020. Les Carabes, Calosomes et Cychres de Genève : détenteurs de mystères évolutifs et maillons essentiels au bon équilibre environnemental. https://museumlab-geneve.ch/2020/07/21/carabes-calosomes-cychres/ Accessed 17.6.2024

Kjernsmo K et al. 2020. Iridescence as camouflage. Current Biology 30(3):551–555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2019.12.013

Goczał J & Beutel RG 2023. Beetle elytra: evolution, modifications and biological functions. Biology Letters 19(3):2022.0559. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2022.0559

Seago AE et al. 2009. Gold bugs and beyond: a review of iridescence and structural colour mechanisms in beetles (Coleoptera). Journal of the Royal Society Interface 6(suppl_2):S165–S184. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2008.0354.focus

Hagen HA 1881. On the color and the pattern of insects. In Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 17:234-267. American Academy of Arts & Sciences. https://doi.org/10.2307/25138651

Lövei GL & Sunderland KD 1996. Ecology and behavior of ground beetles (Coleoptera: Carabidae). Annual review of entomology 41(1):231–256. 10.1146/annurev.en.41.010196.001311