Spotted wing Drosophila – A tiny fly, a big problem and a natural solution

Drosophila suzukii pierces healthy fruit to lay its eggs, causing major damage to berries and cherries. Conventional control methods often fail, but scientists are exploring a natural solution—introducing a specialized parasitoid wasp to keep this invasive pest in check. Can nature help restore balance?

Two male spotted wing Drosophila (Drosophila suzukii) on a berry. Image: Adobe Stock

Classification

- Kingdom

- Animalia

- Phylum

- Arthropoda

- Class

- Insecta

- Order

- Diptera

- Family

- Drosophilidae

- Genus

- Drosophila

- Species

- D. suzukii

The spotted wing Drosophila, with the scientific name Drosophila suzukii, is a fruit fly native to East Asia that has spread to western regions of Asia, North America, South America, Europe, and Africa. It was first detected in Europe in 2008 and has rapidly established itself across the continent, with the first record in Switzerland in 2011.

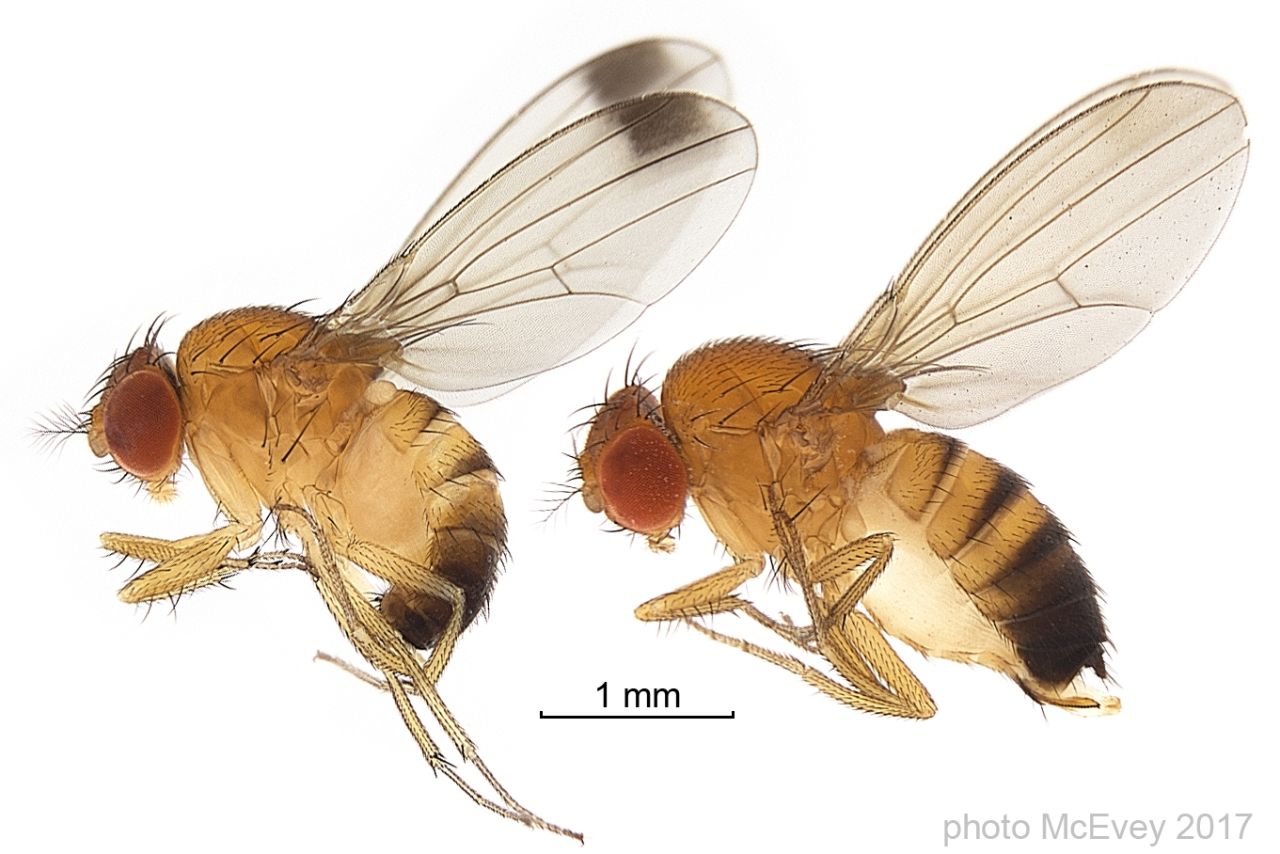

Male (left) and female (right) Drosophila suzukii. Image: Wikimedia/ Shane F. McEvey, Australian Museum, CC License

Unlike most other fruit flies of the genus Drosophila, which mostly target rotting fruit, females of D. suzukii have a secret weapon: a saw-like egg-laying organ, with which they can cut through the skin of ripe, undamaged fruits to lay their eggs inside. Once the larvae hatch, they feast on the fruit, ruining crops like cherries, strawberries, raspberries, blueberries and blackberries. With over 100 different host plants, D. suzukii is a nightmare for farmers!

A female Drosophila suzukii is laying eggs on a cherry. Image: © CABI/Tim Haye

Traditional methods fall short

Insecticides are often ineffective against D. suzukii because the larvae hide inside the fruits, safe from topical applications like sprays. Other management options –such as exclusion nets, mass trapping, repellents, or sanitation measures – can work locally but cannot be used on a large scale outside of agricultural areas. Thus, crops are constantly being re-infested from surrounding wild fruits.

Some farmers grow grapes in gauze bags to prevent D. suzukii from laying eggs inside. Image: Adobe Stock

A natural enemy to the rescue?

An alternative management option is biological control, which is the use of living organisms to control pests. One method, called “augmentative biological control,” involves temporarily and locally boosting the population of a beneficial organism that is already present in the environment. In Italy, it was shown that mass releases of Trichopria drosophilae, a parasitoid wasp that attacks D. suzukii pupae, can help reduce fruit fly numbers. However, releases must be repeated every year, are relatively expensive, and are only locally effective.

Sustainable long-term management options that are effective on a large-scale, and do not add costs to the already impacted fruit farmers are still urgently needed. One option is classical biological control: the introduction and permanent establishment of a natural enemy from the pest’s area of origin to control the pest in all habitats where it occurs. However, to avoid an impact on native species, risk analyses must be done before any introduction, a process that typically takes 7–10 years.

A breakthrough in the fight against D. suzukii

The parasitoid wasp Ganaspis kimorum, is a natural enemy of Drosophila suzukii. Image: © CABI/Koïchi Beltrando

Since 2015, scientists have been searching for the fly’s natural enemies in Asia, where it originated. They identified a promising candidate, the parasitoid wasp Ganaspis kimorum which specifically targets D. suzukii larvae. After years of careful studies in quarantine laboratories – among others at the Swiss centre of the non-profit organisation CABI – to confirm that it won’t harm native species, releases of G. kimorum were conducted in the USA and in Italy starting in 2021 and in France and Israel starting in 2023 – establishment of G. kimorum has alreadybeen confirmed in Italy. In Switzerland, an application to release G. kimorum was submitted to the Federal Office for the Environment in 2022. However, because of rather complex legal issues arising from the Swiss Release Ordinance, only experimental releases were authorized in 2023, limited to the cantons of Jura and Ticino.

With an ever-increasing number of invasive species, it is important to find efficient management options, that do not put native species at risk and can be implemented as soon as possible to reduce the impact of invasive species on food production and the environment. Classical biological control offers a powerful tool to protect crops and ecosystems. The situation in Switzerland shows that to fully harness its potential, countries must find ways to balance safety with efficiency, ensuring that farmers have the tools they need to fight back against invasive species before the damage becomes too great.

References

Seehausen ML et al. 2020. Evidence for a cryptic parasitoid species reveals its suitability as a biological control agent. Scientific reports 5;10(1):19096. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-76180-5

Seehausen ML et al. 2022. Large-arena field cage releases of a candidate classical biological control agent for spotted wing drosophila suggest low risk to non-target species. Journal of Pest Science 95;3:1057-65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-022-01487-3

Stahl JM et al. 2024. Ganaspis kimorum (Hymenoptera: Figitidae), a promising parasitoid for biological control of Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae). Journal of Integrated Pest Management 15;1:44. https://doi.org/10.1093/jipm/pmae036

Haye T et al. 2016. Current SWD IPM tactics and their practical implementation in fruit crops across different regions around the world. Journal of pest science 89:643-51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-016-0737-8