Illustrating insects: Past&Present

Johannes Rudolf Schellenberg's insect drawings are not only beautiful, but also scientifically accurate. Even though photography has become the standard of documentation since Schellenberg's time, drawing insects still has its place in science today.

Insect watercolors of moths and caterpillars by Johann Rudolf Schellenberg, between 1760 and 1800. Image: Wikimedia Commons/Johann Rudolph Schellenberg, CC license

Johann Rudolf Schellenberg (1740–1806) painted a seemingly random detail of a meadow in harmonious colors. The tangle of native plants is teeming with amphibians, reptiles, and insects living in harmony with and alongside each other in this small section of the ecosystem. Near the bottom of the meadow, the arrangement is dense; towards the top, the vegetation opens up to reveal a slightly cloudy sky. The scene appears natural and lively, drawn directly from nature. In fact, every single plant and animal could be named after its species if analyzed closely. Are we looking at a work of art here? Or rather a scientific illustration?

Johann Rudolf Schellenberg (1740–1806) painted a seemingly random detail of a meadow in harmonious colors. The tangle of native plants is teeming with amphibians, reptiles, and insects living in harmony with and alongside each other in this small section of the ecosystem. Near the bottom of the meadow, the arrangement is dense; towards the top, the vegetation opens up to reveal a slightly cloudy sky. The scene appears natural and lively, drawn directly from nature. In fact, every single plant and animal could be named after its species if analyzed closely. Are we looking at a work of art here? Or rather a scientific illustration?

The watercolor painting "Wiesenstück mit Insekten" (Meadow with insects) by Johann Rudolf Schellenberg. Image: ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Graphische Sammlung

A scientist and artist

Schellenberg was a painter, etcher, book illustrator and passionate entomologist from Winterthur. In addition to creating paintings of Swiss landscapes, portraits, pictures of traditional costumes and various book illustrations, he spent his life illustrating entomological and botanical books. Like other illustrators at the end of the 18th century, he stood at the interface between art and science: although the magnificent flower and meadow pieces were conceived and constructed by the artist, precise nature studies and a scientifically accurate representation of the depicted plants and animals form the foundation of the compositions.

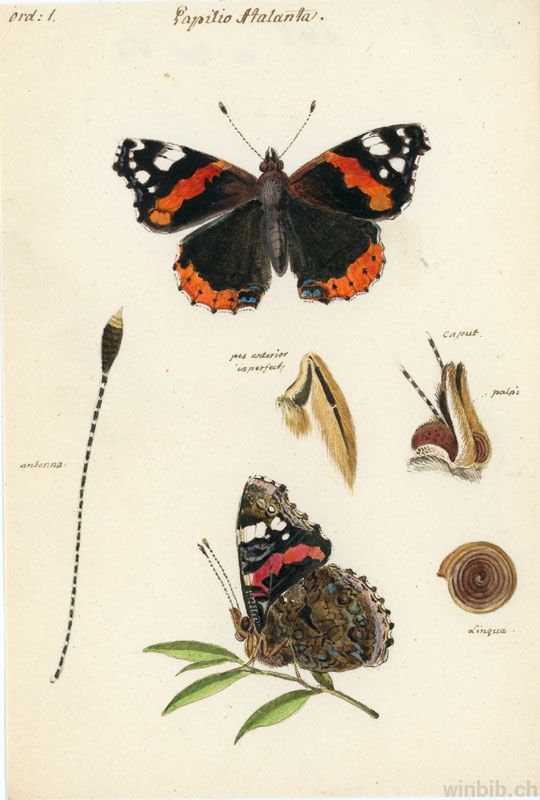

Schellenberg was not only a skilled illustrator but also an enthusiastic entomologist who studied the morphology (outer form) of insects. Here is a depiction of the butterfly red admiral, Vanessa atalanta. Image: © Stadtbibliothek Winterthur, Ms_8°_148-ordo_1-001.

Keeping pace with the times

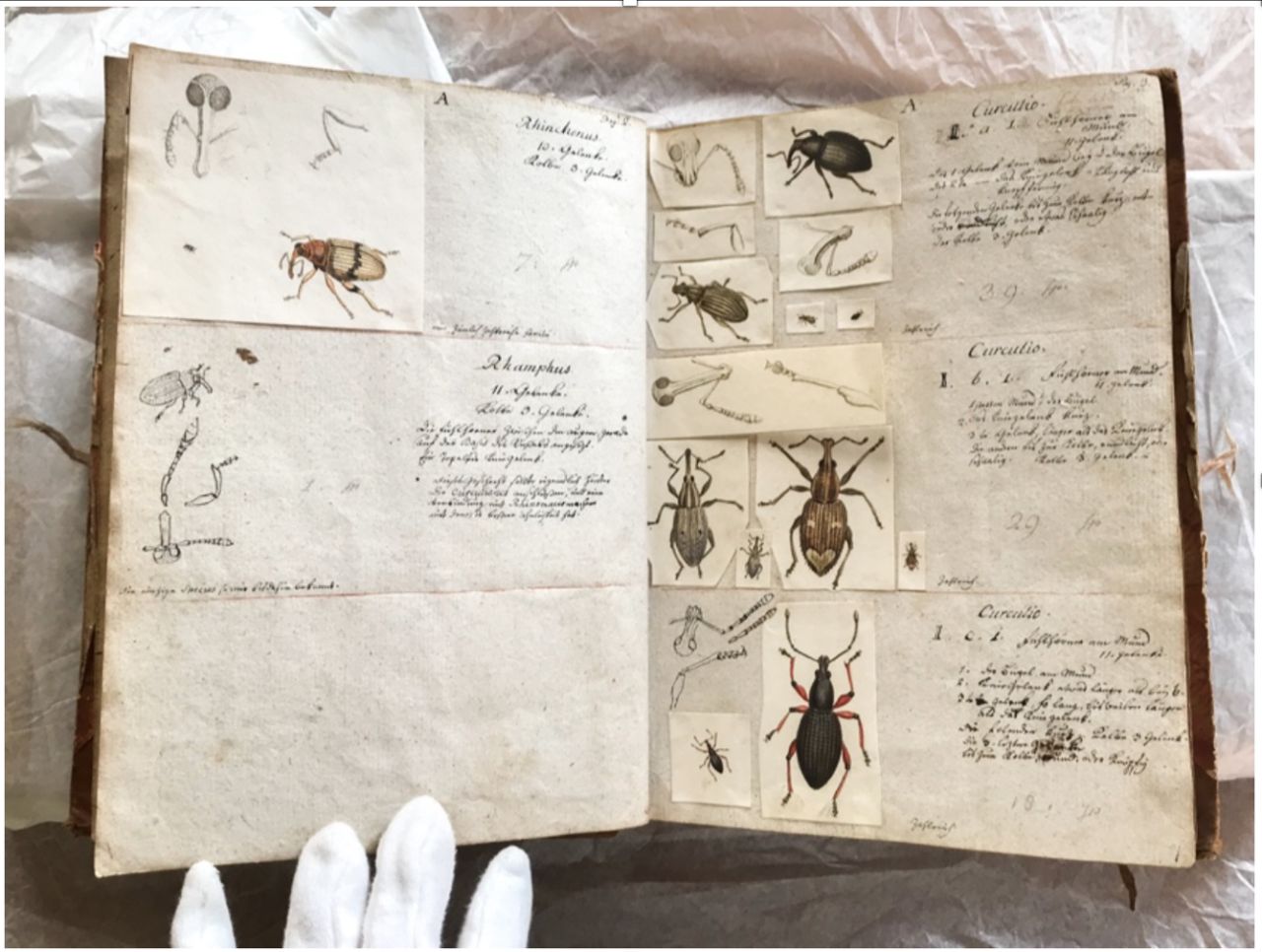

Natural history as a research discipline, as well as insect illustrations, reached their peak in the 18th century. With the introduction of binomial nomenclature*, widely accepted after 1758, questions on the classification of living beings took center stage in research. Many artists, such as Schellenberg, began conducting independent research, specializing, and producing their own works on insects. Over the years, Schellenberg compiled a collection of systematically ordered depictions of insects, which he continually supplemented as new insights were gained. He oriented himself around these individual motifs and repeatedly used them in his illustrations. The City Library of Winterthur (Stadtbibliothek Winterthur) alone now possesses around 4 000 such studies. All of them are organized and named according to classes and genera, accompanied by a legend, and supplemented with a handwritten note on the classification characteristics according to Linnaeus or Fabricius.

Schellenberg arranged his insect images according to the newly developed taxonomy of Linnaeus and Fabricius. He repeatedly used these templates for further works. Image:© Linda Vogel

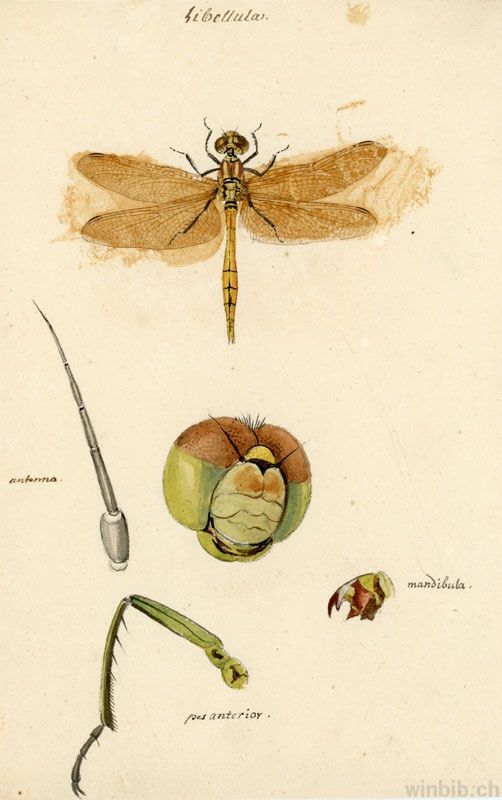

These examples demonstrate that Schellenberg was not merely carrying out commissions but had a genuine interest in the study of insects. This is also indicated by his self-portrait, depicting him with an insect net. Schellenberg often executed the motifs with the highest scientific accuracy. The insects are usually depicted in their actual size, and they are drawn so precisely that even the smallest hairs on their legs can be seen with a magnifying glass. In some cases, Schellenberg even added real wings to the painted insect bodies.

On some watercolors, such as this dragonfly, Schellenberg attached real wings. Image: © Stadtbibliothek Winterthur, Ms_8°_128-Libellula-003.

Competition from photography

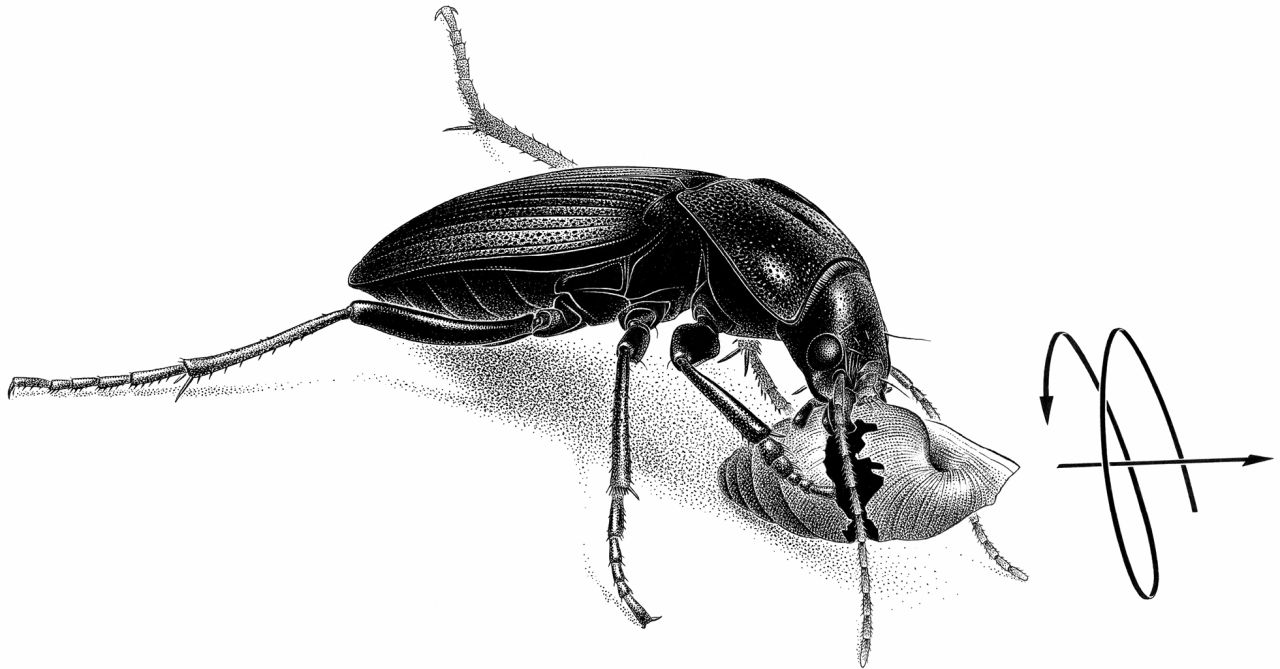

Even though nowadays we can quickly and easily create high-resolution photographs of insects, drawings and paintings still have their place in science. For example, Armin Coray (*1955) from the Natural History Museum Basel has gained a reputation far beyond national borders as an excellent illustrator of insects.

Armin Coray explores the life and morphology of insects to highlight essential features in his drawings. Here is the beetle Licinus depressus, which preys on the snail Chondrina arcadica. Image: Armin Coray, in Baur et al. 2023.

Photographs depict more or less the exterior of an individual insect, with all the flaws and peculiarities of that particular individual. They show everything, including broken antennae, atypical color patterns, and unusual body sizes. An artist like Coray, on the other hand, creates an interpretation of an insect in his work; he emphasizes crucial features, omits the unimportant, thus providing viewers with guidance to understand the insect. It's no wonder that many illustrators, both historically and today, engage in entomological research, possessing in-depth knowledge of the morphology and behavior of insects. Drawing an insect, forces one to look closely in return. To this day, sketching animals and plants from nature remains an indispensable part of biology studies.

*Glossary

Binomial nomenclature: In science, each species is designated with a unique name consisting of two parts. The first part of the name denotes the genus to which the species belongs. The second part, when combined with the first part, forms the complete species name. For example, the butterfly known in English as 'red admiral' has the scientific name Vanessa atalanta. This system was developed in the 18th century by the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus and further advanced by other researchers such as Fabricius.

References

1. Thanner B. 1987. Schweizerische Buchillustration im Zeitalter der Aufklärung am Beispiel von Johann Rudolf Schellenberg. Stadtbibliothek Winterthur.

2. Hünniger D. 2017. Sammeln, Sezieren und Systematisieren. Naturkundliche Verfahrensweisen in der Insektenkunde um 1800. In: Förschler S, Mariss A. (Hrsg.) Akteure, Tiere, Dinge. Verfahrensweisen der Naturgeschichte in der Frühen Neuzeit. Köln/Weimar/Wien.

3. Thanner B, Schmutz H-K., Geus A. 1987. Johann Rudolf Schellenberg: der Künstler und die naturwissenschaftliche Illustration im 18. Jahrhundert. Stadtbibliothek Winterthur.

4. https://www.nmbs.ch/de/museum/ueber-uns/team/armin-coray.html

5. Baur H, Gilgado JD, Coray A. 2023. Prey handling and feeding habits of the snail predator Licinus depressus (Coleoptera, Carabidae). Alpine Entomology 7: 63-68. https://doi.org/10.3897/alpento.7.103164